A Portrait—A Portal: How an antique store find unlocked a fascinating history

by: Bill Chapman

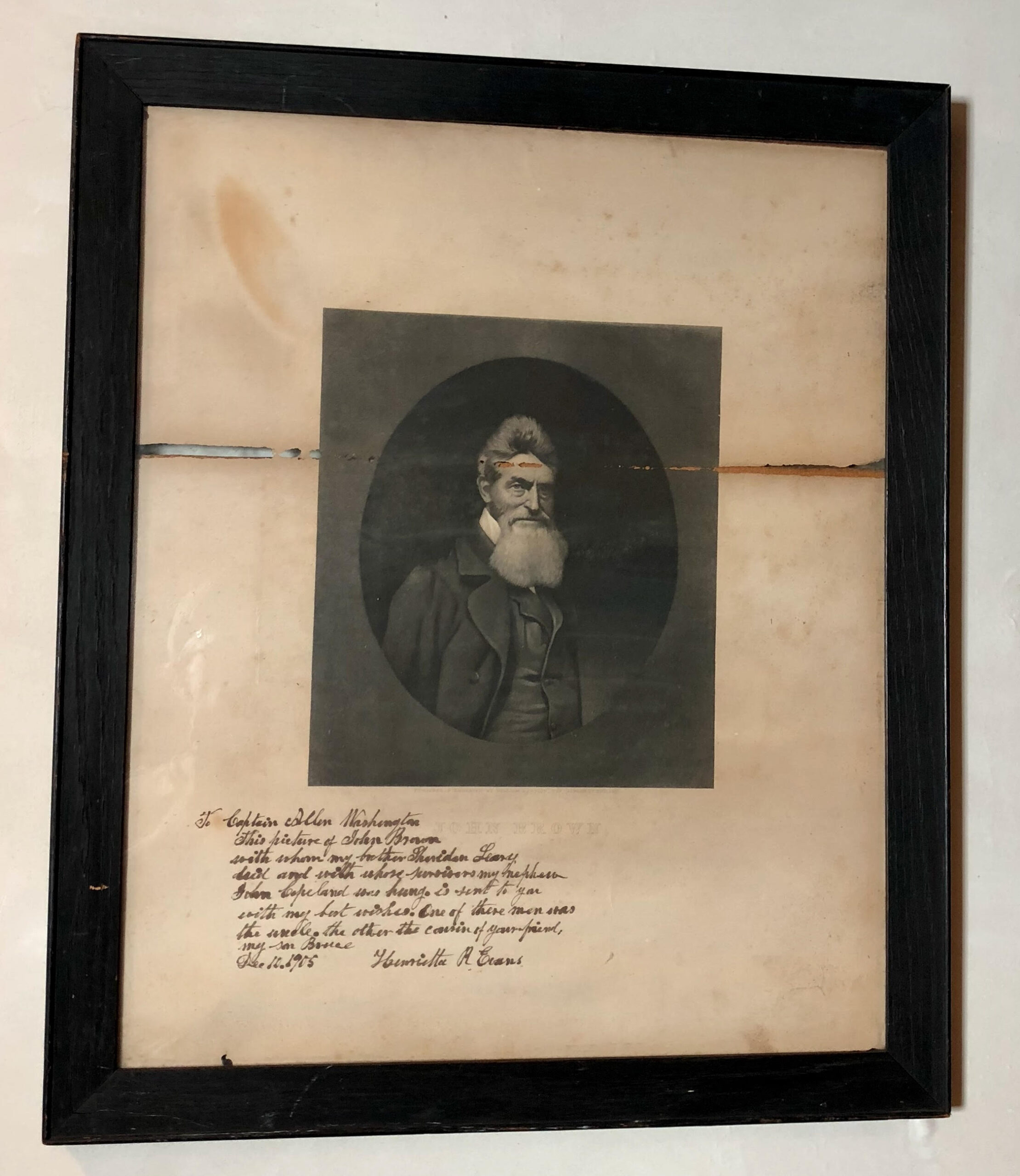

Engravings of abolitionist John Brown are not commonplace in Virginia, so when I

spotted this one in an antique store in Gloucester County, Virginia in 2009, it

immediately caught my eye—as did the fact that, below the old wavy glass, the framed

print had long ago been inscribed in beautiful, bold cursive. As I read the inscription, and even as my heart rate accelerated, I could not have known the learning journey that had just begun for me.

A glance at the price tag startled me. Can that be right? I had barely been in the store

for five minutes and there was much I hadn’t looked at yet, but that would all have to

wait for another day. I took the portrait directly to the counter, paid my $31.50 (feeling

like I was robbing a bank), and quickly left the building with my new, remarkable

treasure.

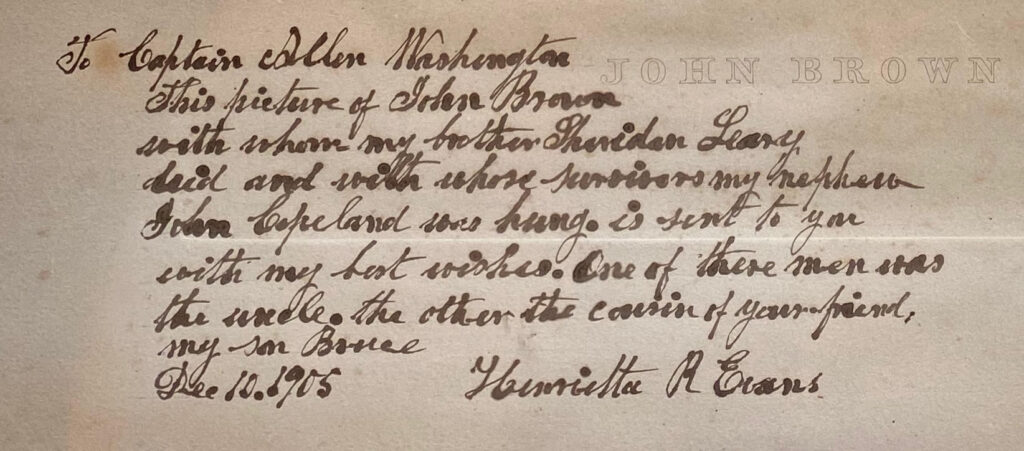

Once safely in the car, I read the inscription to my wife and son:

To Captain Allen Washington

Dec 10, 1905

This picture of John Brown with whom my brother Sheridan Leary died and with

whose survivors my nephew John Copeland was hung, is sent to you with my

best wishes. One of these men was the uncle, the other the cousin of your friend,

my son Bruce

Henrietta R. Evans

Then I shared what I had learned from a quick Google search on my phone while still in

the store. Foremost, Lewis Sheridan Leary and John Anthony Copeland were Black

men. I knew enough about John Brown’s infamous Harper’s Ferry raid to know that the

raiding party was small in number, and that an even smaller number of the men were

Black. My quick search had revealed something else to me, Leary and Copeland were

not escaped slaves who had joined Brown’s army along the way, but free Black

abolitionists. Quickly, I knew that the story told by this inscribed portrait was really not

about John Brown, but about free Blacks fighting for their enslaved brothers—a story

that I had never learned.

Over the ensuing months, I read and learned more and more about Black abolitionists

and a remarkable African American family.

I learned that the Learys and the Evans were two free Black families from Hillsboro,

North Carolina who had been free since the early 1800s. Henrietta Leary (the

inscriptionist) married Henry Evans, and her sister, Sarah Jane, married Henry’s brother,

Wilson Bruce Evans. In 1853, the two families fled persecution in Hillsboro and relocated to Oberlin, Ohio where the men became involved in the abolitionist movement.

In 1858, Henry Evans, Wilson Bruce Evans, Lewis Sheridan Leary, and John Anthony

Copeland (whose mother was an Evans) all took part in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

in which they freed a captured runaway slave and secreted him off to Canada. 37

accomplices, including brothers Henry and Wilson Bruce Evans, were arrested and

jailed for their involvement. Little remembered today outside of Oberlin, this was one of

the boldest and most celebrated abolitionist events of the day—until John Brown and

the raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Veterans of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, Sheridan Leary and John Copeland (who

was educated at Oberlin College) joined Brown’s party of 21 men, three of only five

African Americans to participate. Sheridan was killed during the raid. Copeland was

captured, tried, and hanged with John Brown. On his way to the gallows, Copeland is

reported to have said, “If I am dying for freedom, I could not die for a better cause—I

had rather die than be a slave.”

While John Brown’s legacy is still debated in some circles, the legacy of the African

Americans who joined his effort in the hopes of freeing their brothers is clear cut. It

would be difficult to see them as anything other than heroes. Clearly, Henrietta Evans

held that view when she wrote the inscription on this engraving in 1905. Her husband,

her brother, her nephew, her brother-in-law had all been involved in the effort to end the

enslavement of Blacks.

But their family story didn’t end there.

Her son Bruce Evans (named after his uncle) ran a prominent school for Blacks in

Washington, DC and was an associate of Booker T. Washington. (Henrietta was

probably living in DC with Bruce when she wrote this inscription.) The Captain Allen

Washington, to whom the engraving was gifted, was the commandant at Hampton

Institute, the longtime friend and successor to Robert R. Moton in that role. (Allen

Washington was born in and retired to Gloucester County, Virginia, partly explaining

how the engraving came to be in an antique store there.)

Henrietta’s granddaughter became America’s first internationally acclaimed opera

singer, Lillian Evans Tibbs, known professionally as Madame Evanti. And going

backwards in time for a moment, Sheridan Leary’s widow went on to marry Charles

Langston (also a participant in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue) and became the

grandmother of poet Langston Hughes who inherited and treasured the shawl carried by

Lewis Sheridan Leary at Harper’s Ferry.

The family did great things, generation after generation. Henrietta herself was involved

with W.E.B. Du Bois in the Niagara Movement and was a speaker at the group’s second

gathering in 1906, held in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Just two years later—and three

years after inscribing the John Brown portrait, Mrs. Evans passed away during another

visit to Harper’s Ferry.

For my family, the question immediately became what should become of this portrait,

this portal to a fascinating and important part of our American history that is so rarely

taught. While we love it, it’s a crime for it to be hidden away in our home where it has

neither context nor public visibility.

As timing would have it, the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond had just opened a

John Brown exhibit in 2009. We loaned the portrait for inclusion, and they expressed

interest in having it permanently. But it was important to us that the portrait be in a

collection where it could help tell the story of the Evans and Leary families. For years,

we quietly searched for its rightful home.

Upon learning in 2021 about the formation of the Wilson Bruce Evans Home Historical

Society by Oberlin historians and descendants of the family, and the campaign to

restore the home that brothers Wilson and Henry built together, we knew that this is

where this important portrait should hang. It is out intent, when the Society is ultimately

successful in restoring and opening the home as a museum and education center, to

celebrate that success by donating the portrait to the Society’s collection so it can serve

as a permanent and public portal to this important story.

To ensure that the portrait is an asset without liability, in 2021, we invested in having it

properly restored and conserved by Wendy Cowan at Richmond Conservators of Works

on Paper, who restores noteworthy and historic paper items for museums and

collections around the country. The painstaking and extensive process took a year and

involved carefully cleaning and strengthening the paper, preserving the iron gall ink

inscription, filling paper and art losses from insect damage, and in-painting those fills to

be seamless.

We cheer the important work of the Wilson Bruce Evans Home Historical Society, and

look forward to the day when we can contribute this item to the collection.

Bill Chapman

Bill and Gay Chapman are proud members of the Wilson Bruce Evans Home Historical

Society. They live in Lancaster County, Virginia, where they undertook the restoration of their own family home dating to the 18th century.