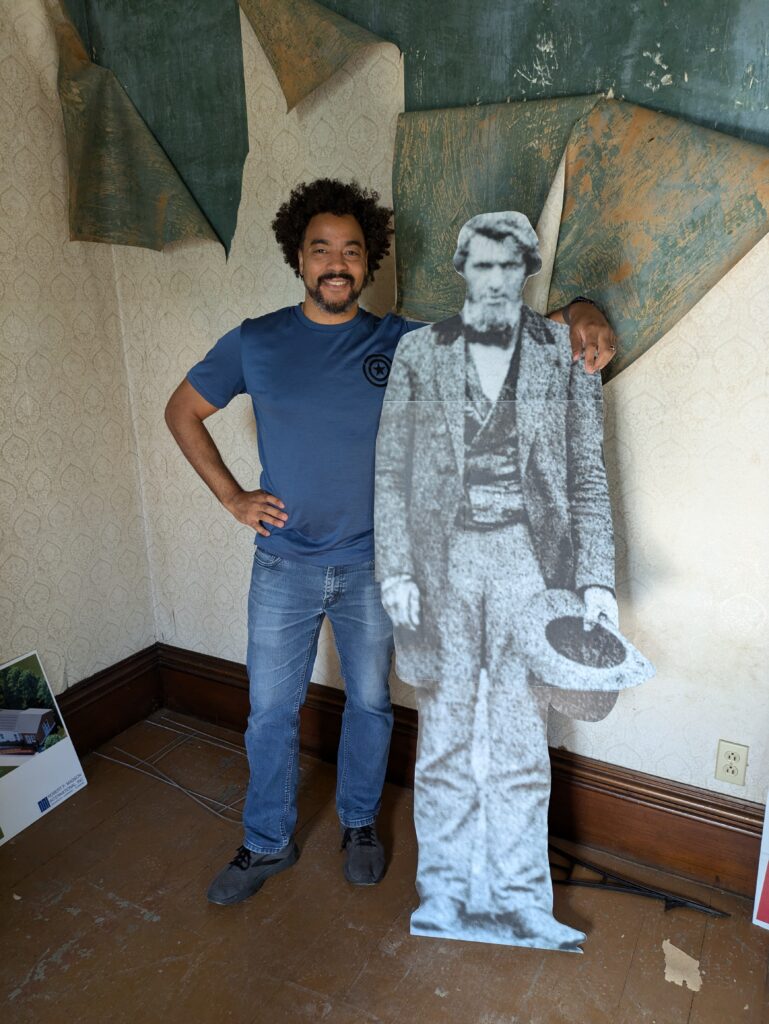

Trustee Wilson Inborden Hughes shares a family story for Juneteenth 2024

Includes with permission excerpts from Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio by Gary J. Kornblith and Carol Lasser (LSU Press, 2018)

Every year as Juneteenth approaches, a wave of self-consciousness settles as I anticipate the dawn of the month celebrating the history of our national, shared African ancestry and my place therein. I doubt it’s just me; it feels like there’s an increase in politically-motivated social pressure to try to forget the negative aspects of our collective American history with regard to race. To me, forgetting that history also denies us an opportunity to fully celebrate what our collective ancestors overcame to build our great nation. I wanted to take an opportunity this year to share a personal story that I carry with me related to my family’s American experience and offer a perspective that I hope summons a sense of pride for Juneteenth, regardless of historical ancestry.

My name is Wilson Inborden Hughes, and I am the namesake of my great, great, great Grandfather, Wilson Bruce Evans and his son-in-law, Thomas Sewell Inborden. This was an honor lost on me as a child; I knew of no other kid with the first name Wilson, and if I didn’t like my first name, my middle name was even worse to go by. (I learned later in life that my mother wanted to call me Wilson Bruce, but my dad learned she dated a guy named Bruce in college and that name was summarily rejected.) I knew I was named after someone who was long dead in my mom’s family, but I didn’t learn the significance of my name until I took my first trip to a family home in Oberlin, Ohio when I was 9.

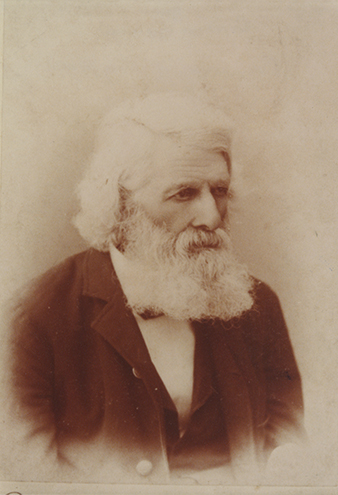

Wilson Bruce Evans was a black man, born free in North Carolina in 1824 and classified on his birth certificate as ‘mulatto’, being identifiably of mixed white/black race. Wilson and his brother Henry were cabinetmakers by trade. Wilson’s sister, Delilah, recommended he, Henry and their wives Sarah Jane and Henrietta move to Oberlin, Ohio, a northern town known for racial tolerance, and they both did so with their wives in 1854, where they took advantage of the opportunities afforded Black people in the North that were denied them where he was born.

Oberlin was one of the unique towns in America that not only allowed Black people to thrive but was an active community in the abolitionist movement that juxtaposed life in the slave-owning southern states. At that time, slavery was still both legal and a way of life, but there was a strong and growing movement to end the awful enterprise.

Wilson Bruce Evans

From the mid-1830s forward, Oberlin gained a well-deserved reputation for harboring freedom seekers fleeing bondage via the Underground Railroad. Most went on to Canada, but some took up residence in Oberlin itself. To the alarm of antislavery Oberlinians, however, Congressional passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 threatened the town’s sanctuary tradition by making any effort to help freedom seekers a federal crime. In response, a mass meeting of residents held in October 1850 avowed their dedication to a higher moral law than any human-made statute and publicly pledged to protect the “fugitive brother . . . in our midst . . . by all justifiable means in our power.” Six years later James Harris Fairchild, a white professor at Oberlin College, proudly observed, “No fugitive was ever taken here and returned to slavery; and this result has been secured without an instance of bloodshed or violence”.

Wilson and Henry grew a thriving business in Oberlin. The brothers also found themselves in a progressive environment where black and white men worked alongside each other and actively sought opportunities to promote racial equality. Wilson was considered ‘more than 50% white’ for legal purposes and that meant he could vote, which he did for the first time in 1855 and thereafter. On Monday, September 13, 1858, an event of chance occurred that changed the lives of Wilson, 22 other men, the town of Oberlin and indeed contributed materially to one of the most important events in American history.

That day in Oberlin, word arrived of the brazen daylight capture of an escaped slave named John Price, who was taken by three men near Wellington, Ohio, while making his way from Kentucky to Canada. At about 1 p.m., Ansel Lyman, a white college student and fervent abolitionist whose father owned a farm in the southern part of town, reported that while walking near Pittsfield at midday he had seen a young freedom seeker being whisked off against his will by three white strangers in a carriage heading toward Wellington. Wellington is roughly 13 miles from Oberlin.

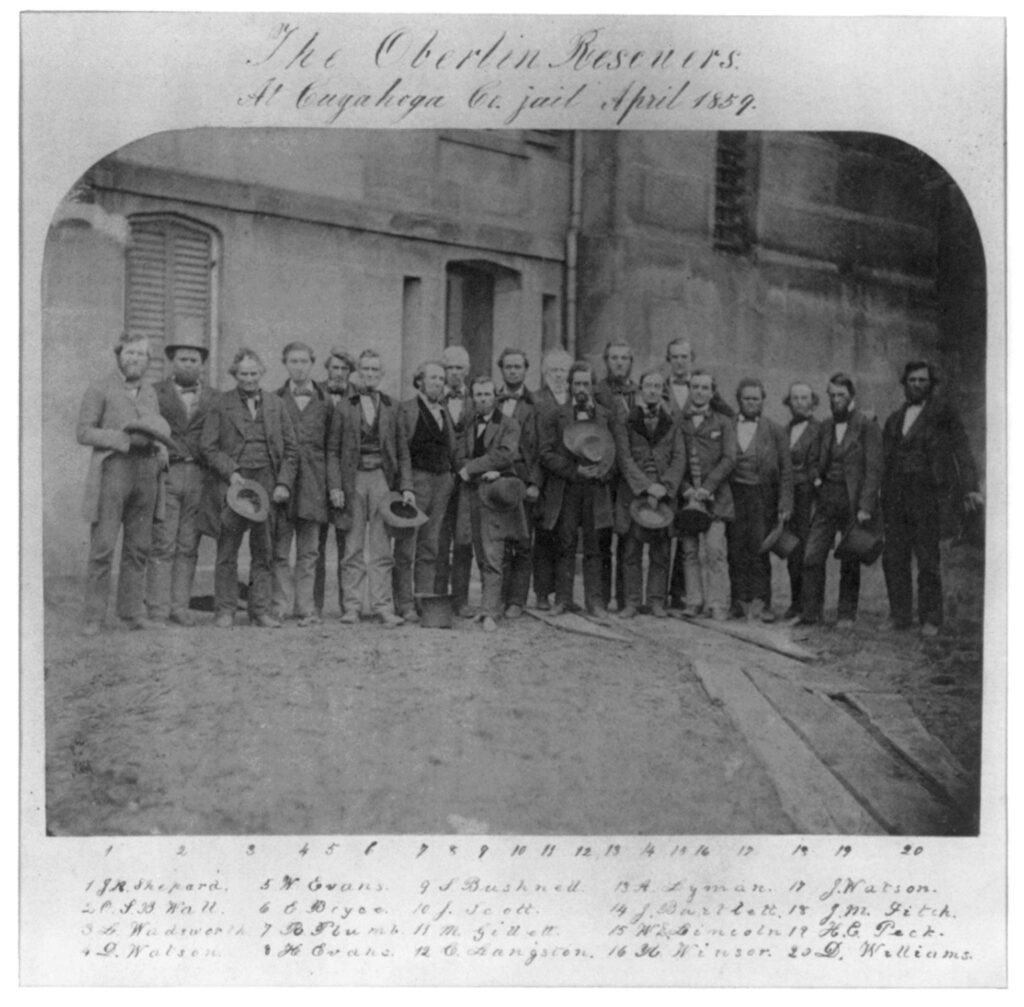

The Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers

To be clear, it was illegal to aid an escaped slave. Nonetheless, after meeting to establish a course of action, hundreds of Oberlin residents, including Wilson Bruce Evans, his brother, and his brother-in-law Lewis Sheridan Leary raced to Wellington to keep their pledge to freedom. But 22 of the townsfolk from Oberlin rushed to Wellington and surrounded the hotel in which Mr. Price was held captive. After failed negotiations to free him, the townsfolk stormed the hotel, restrained the slave catchers (including a US Marshal acting under authority of the Slave Act) and freed Price without damage or harm. Price was hidden away in Oberlin until his eventual escape to freedom.

Oberlinians viewed Price’s escape as a wonderful triumph for the community’s abolitionist principles. Upon their return to Oberlin, the Rescuers were welcomed by impromptu rallies near the center of town. The evening’s joyous mood was tinged with anger, however, and “it was voted with deafening unanimity that whoever laid hands on a black man in this community, no matter what the color of authority, would do so at the peril of his life.”

The federal government saw things differently. 34 men, including Wilson Bruce and Henry Evans, were indicted on a charge of “direct participation in rescuing a fugitive from service”. Half of those indicted were men of color. The men were rounded up and jailed, to await trial for their crime. Because the federal government lacked its own holding facility near Oberlin, the defendants were transferred to the Cuyahoga County jail, under the supervision of Sheriff David L. Wightman, a Republican sympathetic to the Rescuers. Over the weekend of April 16-17, 1859, “Hundreds of ladies and gentlemen of the highest standing called on the Oberlin prisoners,” reported the Cleveland Herald. “On all sides they were greeted with assurances of sympathy and respect.”

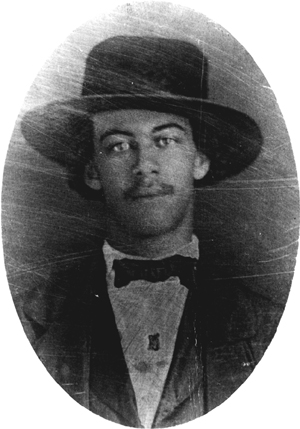

Lewis Sheridan Leary

Only two of the men were prosecuted and found guilty of the crime, one white and one black, before charges against the other men – including Wilson and Henry – were dropped. But the Oberlin-Wellington rescue had embodied a spiritual tide that was sweeping over the nation. The rescue event itself and similar dramas were occurring more regularly throughout the United States. Indeed, Wilson’s brother-in-law, Lewis Sheridan, found his way to a radical white Freedom Fighter named John Brown, who had plans to free slaves through unpeaceful means in Virginia. Both men would die there in the famous Raid on Harpers Ferry. These events, one peaceful and one violent, would become seminal ones that helped push the United States into Civil War.

The story of John Price, Wilson and Sarah Jane, Henry and Henrietta Evans, Ansel Lyman, James Fairchild, Lewis Sheridan, and the hundreds of men and women of Oberlin and Wellington is a uniquely American one. It is a story of the pain of the past, but it is also a story of the spirit of freedom and justice that Americans continue to believe in and celebrate. My hope for those reading this story as they recognize that the remarkable townsfolk of Oberlin are not unique to Oberlin or a time past, but they are unique to America, and we all can embody the spirit of their commitment to freedom.

Wilson Bruce Evan’s legacy is now honored through the Wilson Bruce Evans Home Historical Society, which celebrates the life and times of Mr. Evans and his compatriots. I’m a trustee on the board of the Society; given my namesake it was of course a family obligation. We’re in the process of turning Wilson’s house – a historical landmark – into a museum that tells the stories of Oberlin’s freedom fighters and their part in the Underground Railroad to visitors every day. If you’re interested in learning more our goals or the Oberlin-Wellington rescue, we invite you to check us out at https://evanshhs.org.

Historical Marker Dedication for Wilson Bruce Evans Home

So, from me, my brother, Lewis Sheridan Hughes, my family, and the Wilson Bruce Evans Historical Society, I invite everyone to celebrate themselves and their and their family’s contributions to a More Perfect Union during Juneteenth.