The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

Adapted with permission from Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio by Gary J. Kornblith and Carol Lasser (LSU Press, 2018)

From the mid-1830s forward, Oberlin gained a well-deserved reputation for harboring freedom seekers fleeing bondage via the Underground Railroad. Most went on to Canada, but some took up residence in Oberlin itself. To the alarm of antislavery Oberlinians, however, Congressional passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 threatened the town’s sanctuary tradition by making any effort to help freedom seekers a federal crime. In response, a mass meeting of local residents held in October 1850 avowed their dedication to a higher moral law than any human-made statute and publicly pledged to protect the “fugitive brother . . . in our midst . . . by all justifiable means in our power.” Six years later James Harris Fairchild, a professor at Oberlin College, proudly observed, “No fugitive was ever taken here and returned to slavery; and this result has been secured without an instance of bloodshed or violence.

On Monday, September 13, 1858, news reached downtown Oberlin of an audacious kidnapping of an African American in broad daylight. About 1 p.m., Ansel Lyman, a white college student and fervent abolitionist whose father owned a farm in the southern part of town, reported that while walking near Pittsfield at midday he had seen John Price–a young freedom seeker residing in Oberlin–being whisked off against his will by three white strangers in a carriage heading toward Wellington. A crowd promptly gathered in front of African American John Watson’s grocery on South Main Street to decide on a course of action.

Keeping a pledge that he had made years before to assist all freedom seekers in distress, Watson raced off to Wellington to rescue Price from the prospect of re-enslavement. Hundreds of other Oberlinians followed Watson’s lead, many riding by horse and buggy but others going on foot. Whites and Blacks occasionally traveled together, and a few women participated alongside men. Several of the men, especially those of color, carried guns.

When Watson arrived in Wellington, John Price and his captors were passing time at Wadsworth’s Hotel, awaiting the arrival of a late afternoon train headed south toward Columbus–the first stop of a planned trip to restore Price to his purported owner in Kentucky. Soon a large, interracial throng surrounded the building, located on Wellington’s town square, and loudly demanded Price’s release. The men holding Price included Anderson Jennings, a Kentuckian who claimed legal authority to represent Price’s “owner,” and Jacob K. Lowe, a Columbus-based U.S. deputy marshal for Ohio’s Southern District, who carried with him a federal warrant for Price’s arrest under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. At one point, Jennings brought Price out on a balcony overlooking the assembled multitude, and Price publicly acknowledged that he had been a slave “and supposed he would have to go back” to his master. But the crowd remained determined to save him from a return to bondage. African American John Anthony Copeland brandished a gun, prompting Jennings to retreat inside. Ultimately it took force to rescue Price, although bloodshed was averted. As daylight turned to dusk, members of the crowd stormed the hotel, grabbed Price, and put him in a buggy that carried him safely back to Oberlin. He spent the night and the following few days hidden from sight in James Harris Fairchild’s stately house on South Professor Street. What happened to Price afterwards is undocumented. Presumably he made his way across Lake Erie and into Canada, perhaps guided by John Anthony Copeland, who himself would later take part in John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry. John Price was never seen on the streets of Oberlin again.

Most Oberlinians viewed Price’s escape as a wonderful triumph for the community’s abolitionist principles. Upon their return to Oberlin, the Rescuers were welcomed by impromptu rallies near the center of town. The evening’s joyous mood was tinged with anger, however, and “it was voted with deafening unanimity that whoever laid hands on a black man in this community, no matter what the color of authority, would do so at the peril of his life.”

The Oberlin Evangelist, the institutional voice of Oberlin Congregationalism, defended the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue on the grounds that, although it may have violated the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, it abided by “the Higher Fugitive Law” of “the fifth book of Moses: ‘Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped from his master unto thee; he shall dwell with thee even among you . . . in one of thy gates where it liketh him best: that shalt not oppress him.’–Deut. xxiii: 15,16.” “The movement was doubtless very imprudent,” the paper declared, “but there are higher virtues than that low prudence which men are wont to honor.”

Federal authorities disagreed, and a federal grand jury was empaneled in Cleveland to bring charges against the individuals who rescued John Price. On December 6, the grand jury handed down indictments of thirty-seven men. Thirty-four were charged with direct participation in “rescuing a fugitive from service,” while three were charged with “aiding, abetting and assisting to rescue a fugitive slave from service and labor.” Twenty-two of the accused were from Oberlin or Russia Township; twelve from Wellington; one each from the nearby towns of Pittsfield and Penfield; and one–Charles Langston, John Mercer Langston’s brother–was a resident of Columbus with longstanding ties to Oberlin. Some had played prominent parts in the Rescue, but the selection of others for prosecution was more surprising. From the time the grand jury announced its decision, critics contended that partisan politics influenced the pattern of indictments. (Oberlin was a bastion of antislavery Republicans; the jury was composed entirely of Democrats.) Race also mattered. Fully half of the indicted Oberlinians were men of color, including brothers Wilson Bruce Evans and Henry Evans, who had moved from North Carolina to Oberlin four years earlier.

After the indictments came down, Matthew Johnson, the U.S. Marshal for the Northern District of Ohio, traveled to Oberlin to inform the accused of the charges and order them to appear in court. The men he located put up no resistance and agreed to cooperate with legal authorities. Five of the indicted individuals escaped arrest, however, and never faced judicial proceedings.

On December 8, fourteen Oberlinians appeared in federal court in Cleveland to enter pleas of not guilty before U.S. District Judge Hiram V. Willson. Through their attorneys, they asked the court to proceed to trial immediately–a request that caught the federal prosecutor off guard. Judge Willson scheduled the trial for the spring term of 1859. He also released the accused Rescuers on their own recognizance rather than requiring them to post bail.

The first of the indicted men to go on trial was Simeon Bushnell, a twenty-nine-year-old white clerk, new father, and former student in the College’s preparatory department who worked for printer James M. Fitch, his brother-in-law and fellow defendant. Bushnell’s involvement in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue was undeniable: he had driven the buggy that took John Price back to Oberlin after he was retrieved from Wadsworth’s Hotel. Defense lawyers raised questions about the true identity of John Price, the legality of his capture and detainment, and the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act, but they never challenged the basic facts of Bushnell’s role in Price’s escape. The trial lasted from April 5 through April 15, 1859. After brief deliberations, the jury, which at the insistence of the prosecutor excluded anyone with antislavery sympathies, found Bushnell guilty as charged.

Although this verdict was expected, what happened next was not. When the prosecutor moved to try African American Charles Langston, Judge Willson announced that the same set of jurors that had just convicted Bushnell would hear Langston’s case and those of the other defendants. Defense attorneys objected that this irregular procedure would gravely disadvantage their clients and signaled their intention to file a formal challenge when the court reconvened after a weekend break. At the prosecutor’s urging, Willson remanded the twenty defendants then in the courtroom to the custody of Matthew Johnson, the U.S. Marshal, until the court reassembled. Although Johnson, in the words of the Cleveland Leader, “offered to let them go home, if they would give him their parole of honor that they would return on Monday morning,” they unanimously refused. To draw attention to the court’s unfairness and to rally public support for their cause, they chose to go to jail.

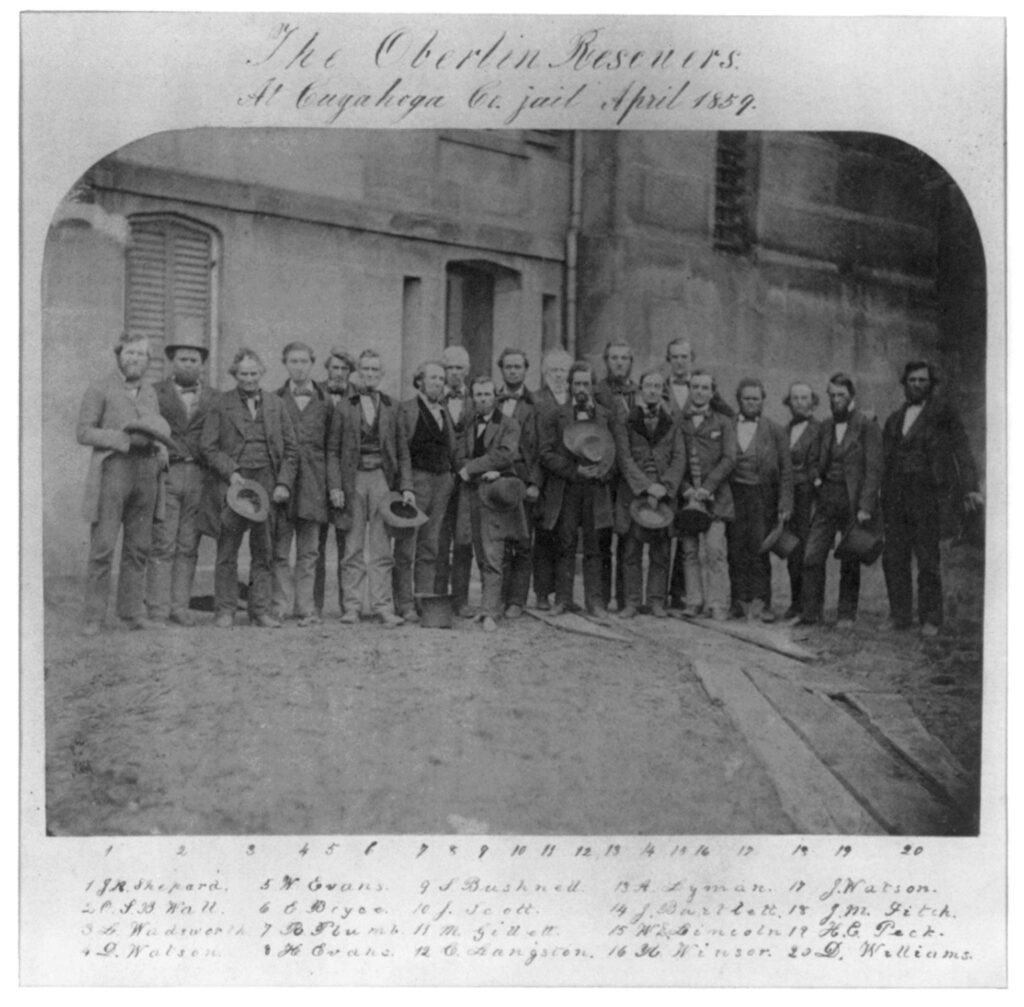

Because the federal government lacked its own holding facility in Cleveland, the defendants were transferred to the Cuyahoga County jail, under the supervision of Sheriff David L. Wightman, a Republican sympathetic to the Rescuers. Over the weekend of April 16-17, “Hundreds of ladies and gentlemen of the highest standing called on the Oberlin prisoners,” reported the Cleveland Herald. “On all sides they were greeted with assurances of sympathy and respect.”

Judge Willson reversed himself on April 18, agreeing to seat a new jury to hear Langston’s case. But the Rescuers remained in custody in “Wightman’s Castle,” as the county jail was nicknamed. Most of the incarcerated men found life behind bars surprisingly comfortable, at least initially. Rather than being kept under lock and key, they were free to move about the jail and allowed access to the building’s courtyard and rooftop for exercise. They found solace in song and prayer. Yet peace and tranquility were elusive. The building housed not only suspected criminals but also the mentally ill, whose “howlings and ravings” regularly disrupted the Rescuers’ slumber.

Federal authorities employed a divide-and-conquer strategy to try to break the defendants’ spirit of solidarity and resistance. Over time, the charges against two men were dropped on technicalities, and the four incarcerated Wellingtonians were released on bail or their own recognizance. Of the twenty men remanded to the marshal’s custody on April 15, only fourteen remained in jail a month later: eight whites and six persons of color, all associated with Oberlin.

Although the legal case against Charles Langston was weaker than that against Bushnell, the verdict, returned on May 10, was the same: guilty. Before pronouncing sentence, Judge Willson–in keeping with standard practice–offered Langston a chance to address the court in his own behalf. Langston took full advantage of the opportunity and eloquently denounced the joint injustices of slavery and racism in the United States. “The colored man is oppressed by certain universal and deeply fixed prejudices,” he declared. “And the prejudices which white people have against colored men, grow out of this fact: that we have, as a people, consented for two hundred years to be slaves of whites.” Applying this general analysis of American racism to the specifics of his own case, Langston argued that deep-seated prejudice against people of color like himself had contaminated the entirety of the court’s proceedings. “The jury came into the box with that feeling,” he asserted. “The gentlemen who prosecuted me have that feeling, the Court itself has that feeling, and even the counsel who defended me have that feeling.” As a result, Langston concluded, “I should not be subject to the pains and penalties of this oppressive law, when I have not been tried, either by a jury of my peers, or by a jury that were impartial.”

To Langston’s surprise, the judge reacted favorably to his remarks. “You have presented considerations to which I shall attach much weight,” Willson said, and he sentenced Langston to twenty days in the Cuyahoga County Jail and a fine of $100–a significantly lighter punishment than the sixty days in jail and $600 fine Willson had imposed on Simeon Bushnell.

An effort by defense attorneys to circumvent the U.S. District Court by appealing to the Ohio State Supreme Court for writs of habeas corpus failed when the latter body ruled against the Rescuers on May 30. Meanwhile, Judge Willson delayed hearing future cases pertaining to the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue until the start of a new court term in early July. The Oberlin inmates could have posted bond and headed home for the duration, but for reasons of both principle and political effect, they decided to remain in custody.

To fend off boredom in jail, printers James M. Fitch and Simeon Bushnell decided to publish a newspaper. The first and only issue of The Rescuer appeared on July 4, 1859. In an article titled “A Few Words about Ourselves (The ‘Rescue Company’),” the inmates offered a collective profile in terms of their geographical origins (three from North Carolina, four from New York, one each from Ohio, Louisiana, and South Carolina, three from England), their marital and family status (ten were married, with a total of thirty-seven children), their occupations (two printers, three upholsters and cabinetmakers, one shoemaker, one harness maker, one school teacher and student, one lawyer, one college professor and minister), and their religious affiliations (eight Congregationalists, one Methodist, one Episcopalian)–but not in terms of their physical appearance or racial ancestry. They were determined to project to the outside world the impression of a united front irrespective of color.

On the afternoon of July 6, 1859, the months-long drama in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio came to an abrupt end. In return for a promise by Lorain County authorities to drop kidnapping charges brought against the men involved in the seizure of John Price the previous September, the U.S. district attorney agreed to abandon any further prosecution of the indicted Rescuers. Judge Willson reluctantly acceded to the deal, and before nightfall twelve of the thirteen Oberlinians departed for home, leaving behind Simeon Bushnell, who remained in jail to finish his sentence.

When the Rescuers arrived by train in the early evening, a jubilant crowd greeted them at the local depot, and the liberated Rescuers then paraded triumphantly up Main Street to the Congregational Church. “The vast building was in a moment crowded to its utmost capacity,” reported James M. Fitch. “It was a grand and cheering sight.” For the next four hours, an array of orators addressed the assembled multitude, most of them portraying the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue and subsequent trial and incarceration as a redemptive episode in the holy struggle of good versus evil. Yet John Watson, who had led the race to Wellington to rescue John Price the previous September, raised questions about the extent of the community’s moral righteousness. “Even here in Oberlin have we wolves in sheep’s clothing,” he observed. “They come to us with fawning fingers and smiling lips, while in their hearts they are plotting the most piratical and inhuman atrocities, and plotting them against us, their next-door neighbors, who never lifted a finger to harm them or theirs, and never would.” He decried Oberlin’s tolerance of “these traitors” and argued that “if emphatic leave of absence had been given these men long ago, we should have been saved all the trials of the last year.” Watson closed his speech on a more conciliatory and optimistic note, however. “I rest in this confidence,” he said, “that . . . whatever you may have done in the past, henceforth you will show oppression no quarter.”

As midnight approached, the audience at First Church, still in a celebratory mood, passed a resolution praising the Rescuers “who, rather than give the least countenance to the Fugitive Slave Act, have lain eighty-four days in Cleveland jail.” “To our faithful friends,” the townspeople avowed, “we express our warmest gratitude and our unqualified commendation for the firmness, the wisdom, and the fidelity with which they have maintained our common cause.” Toward the end of the following century, Nat Brandt would title his book about the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue The Town That Started the Civil War in tribute to Oberlin’s role in propelling the conflict over slavery to the fore of the nation’s moral and political agenda.